There’s so much talk about the Green Belt – particularly here in Barnet on the edge of London where it literally shapes the town. It also means a lot to us emotionally, so let’s take a closer look.

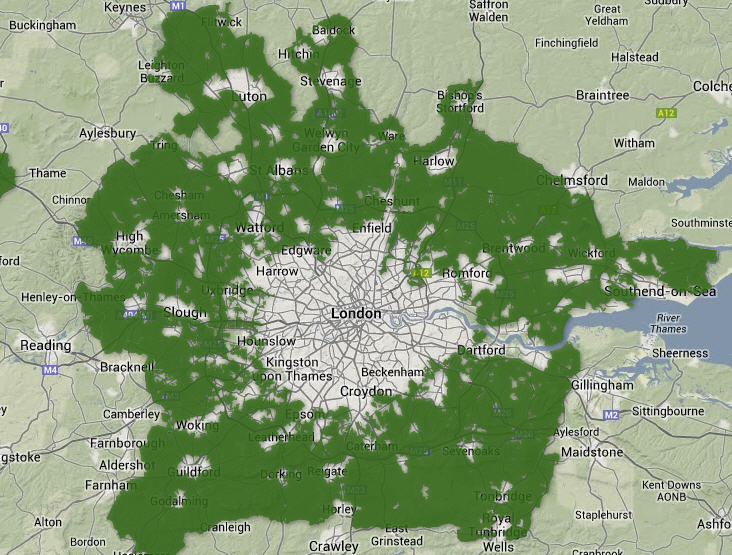

To use its full name, the Metropolitan Green Belt encircles London with strict planning regulations to keep it open and undeveloped. It extends across a much larger area than you might realise – up to 35 miles deep in places. The Green Belt is three times the size of London and covers most of Hertfordshire and Surrey and extends beyond Southend. Within London, 20 percent of the area is classed as Green Belt.

The Metropolitan Green Belt is the largest of 14 Green Belts in the UK (you can see them mapped here). The National Planning Policy Framework stipulates “the fundamental aim of Green Belt policy is to prevent urban sprawl by keeping land permanently open; the essential characteristics of Green Belts are their openness and permanence.”

According to official planning regulations “Inside a Green Belt, approval should neither be given, except in very special circumstances, for the construction of new buildings, or for the change of use of existing buildings, nor for purposes other than agriculture, sport, cemeteries, institutions standing in extensive grounds, or other uses appropriate to a rural area.”

Aside from restricting development and maintaining local agriculture, there are also clear environmental benefits. According to the London Green Belt Council, “Green Belt protection has ensured Londoners enjoy open land and countryside in and near the city. Many areas of Green Belt are country parks or playing fields, they support sport and recreation, tourism and health – including reducing stress by providing peaceful, breathing spaces and 9,899km of public rights of way” and there are eco-system benefits, “Different types of open land provide multiple eco-system benefits which include urban cooling, improved air quality, flood protection and carbon absorption (especially woodland areas), as well as local food production.” They also help future proof London as it grows into a higher density city, “so more people come to rely on protected green spaces for the many benefits they provide. Land protection policy recognises that these protected lands may be, and in fact stipulates that they should be, enhanced to provide more benefits in future.”

How did Green Belts evolve?

The idea of keeping land open around towns was mentioned in the Bible and Elizabeth 1 tried to impose a three-mile Green Belt around London and Westminster in 1593 to limit its size and to help prevent the plague spreading. However, London steadily increased in size and by the early 20th century, following Victorian industrialisation and the advent of suburban railways, London and other cities had grown rapidly. Planners and policy makers never lost sight of finding ways to contain development. In 1890 Ebenezer Howard, founder of the Garden City movement, recommended “always preserving a belt of country around our cities”. The Ringstrasse in Vienna was seen as an inspiration for this – a park cum green boulevard encircling the city using land that became available when the old walls were demolished in 1857.

Howard’s ideas inspired the 1919 Town and Country Planning Association which called for towns to be enclosed by a rural belt and in 1935 there were proposals by the Greater London Planning Committee to “provide a reserve supply of public open spaces and of recreational areas and to establish a green belt or girdle of open space”. This was backed up with a Green Belt loans scheme introduced to enable local authorities to purchase 11,400ha of open land. Three years later in 1938 this reserved land around London was given permanent protection by the Green Belt (London and home counties) Act.

The Town and Country Planning Act of 1947 permitted local authorities to designate areas as Green Belt and show them in their town plans and in 1955 the Ministry of Housing and Local Government allowed them to be formally defined. Circular 42/55 outlines three functions: “To check urban growth; to prevent neighouring settlements from merging and to preserve the special character of a town”. By now the original vision of a mile-wide band of parkland had evolved into a considerably larger buffer recommended to be “several miles wide” (often up to 10 miles) which continued to grow and the original purpose has been rigorously upheld by more recent planning legislation.

To give an idea of how it is made up, 26 percent of London’s Green Belt is environmentally protected recreational land like playing fields, country parks (like Trent Park) and ancient woodland (such as Hadley Woods). There are also nearly 10,000 km of public rights of way like the Dollis Valley Greenwalk. However, two-thirds of the Green Belt is agricultural land, often used for intensive or mono-cultural farming, so not particularly environmentally friendly or physically attractive. It’s not always that “green and pleasant”.

Barnet and the Green Belt

Being situated on the edge of London we are physically aware of the Green Belt and have a powerful attachment to it emotionally (particularly being able to look out on it every day and benefit from its presence). We are consequently very sensitive to threats being made to it. Residents have been vigilant about planning applications (like the unsuitable plans for the Ark Academy on the Underhill Stadium site). The Barnet Society was founded in 1945 primarily to play active role defending the Green Belt (whether brownfield or greenfield sites),

“In practice, however, the last few years have seen permission granted for a range of developments, such as conversion of historic meadow to school all-weather playing field, and of a stables to a horseball centre. Although these spaces have remained open, their natural green character has been eroded or lost altogether.”

“… we accept that changes have inevitably occurred, most notably in our area the disappearance of working farms and their replacement by garden centres, leisure facilities and the like. We also acknowledge that this process is likely to continue.”

“Our wish would therefore be for the continuing and rigorous protection of indigenous and historic natural environments, but – if development cannot be avoided – the enforcement of the highest design and sustainability standards.”

Here is detailed map showing the Green Belt and current threats to it. You can enlarge it to see the local area clearly.

The future

It is worth remembering that Green Belts were formalised after the Second World War when many people had been “bombed out” of London by the Blitz. These new planning restrictions were introduced in tandem with the New Towns Act of 1947 and the construction of seven large towns within easy reach of London with more following in the 1960s and ‘70s.

In the light of the current demand for housing, the Green Belt approach has its detractors who see it a simplistic way of controlling urban spread. Recent studies show that compromises like a “green web” or “green wedges” with corridors of development (such as the London-Stansted-Cambridge corridor proposed by the London School of Economics). One of the aims is help prevent the current piecemeal erosion of the Green Belt.

With population growth, planners need to balance rising demands for new housing with the vital benefits of healthy open spaces. It’s one of the biggest challenges we face. However, to conclude, poet Andrew Motion offers this vivid description of what the southeast of England would be like without the Green Belt:

“Since about 1940, the population of Los Angeles has grown at about the same rate as the population of London. Los Angeles is now so enormous that if you somehow managed to pick it up and plonk it down on England, it would extend from Brighton on the south coast to Cambridge in the north-east. That’s what happens if you don’t have a green belt.”

Really interesting: thanks Lucy

Glad you enjoyed the piece Lorna and thanks for the comment.